By Yasmin Chaudhary — The Inkwell Times

We love a gangster story.

We love the suits, the power, the myth of control, the idea of a man who rises from nothing and bends the world to his will. Shows like The Godfather of Harlem pull us in because they feel epic—almost operatic. But somewhere along the way, admiration quietly replaces accountability.

What we rarely ask is why these stories exist at all—and who never had the privilege to choose a different path.

It’s easy to judge from the safety of distance. It’s easy to call someone a criminal when your own survival was never on the line. But when poverty, racism, segregation, and state violence shape the world you’re born into, morality becomes complicated. Choices shrink. Options disappear. And sometimes, survival itself becomes criminalized.

This isn’t about glorifying gangsters. It’s about understanding how systems create them—and how society consumes their stories while ignoring the conditions that made them inevitable.

The Romance of the Gangster: A Cultural Obsession

American culture has a long-standing fixation on mobsters and gang leaders. From The Godfather films to modern prestige television, these figures are often portrayed as:

- Charismatic antiheroes

- Men of “honor” operating outside corrupt systems

- Symbols of rebellion against authority

But this framing is selective. It isolates individuals from the systems that constrained them, while also softening the violence they inflicted.

The danger isn’t storytelling—it’s mythmaking. When crime becomes aesthetic, the victims disappear.

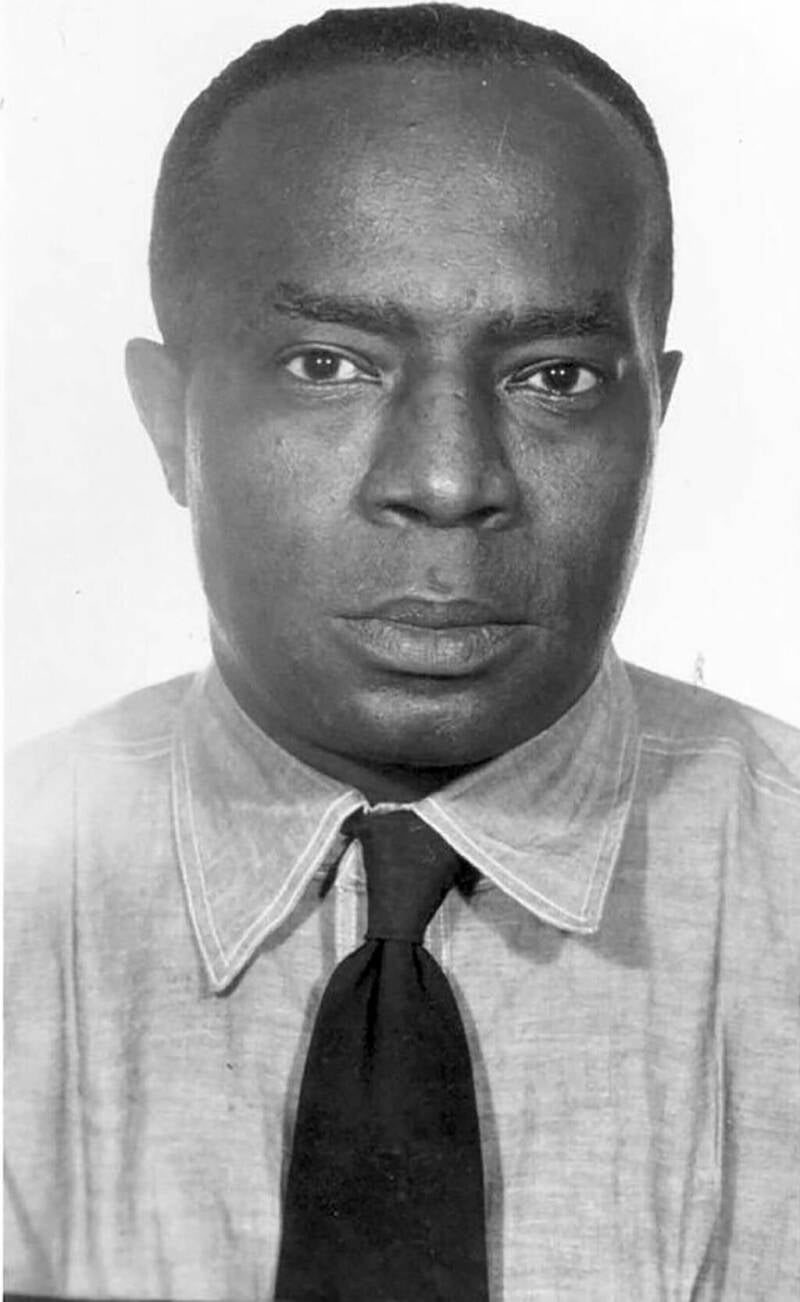

Who Was Bumpy Johnson — Fact, Not Legend

Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson was a real figure, not just a television character.

The facts:

- Born in 1905 in Charleston, South Carolina

- Moved to Harlem during the Great Migration

- Became a major power broker in Harlem’s illegal economy, especially numbers gambling and heroin trafficking

- Worked closely with the Italian Mafia, including Lucky Luciano

- Spent much of his life in and out of prison

He was undeniably violent. He profited from drug distribution that devastated Black communities. People died because of the world he helped maintain.

That truth matters.

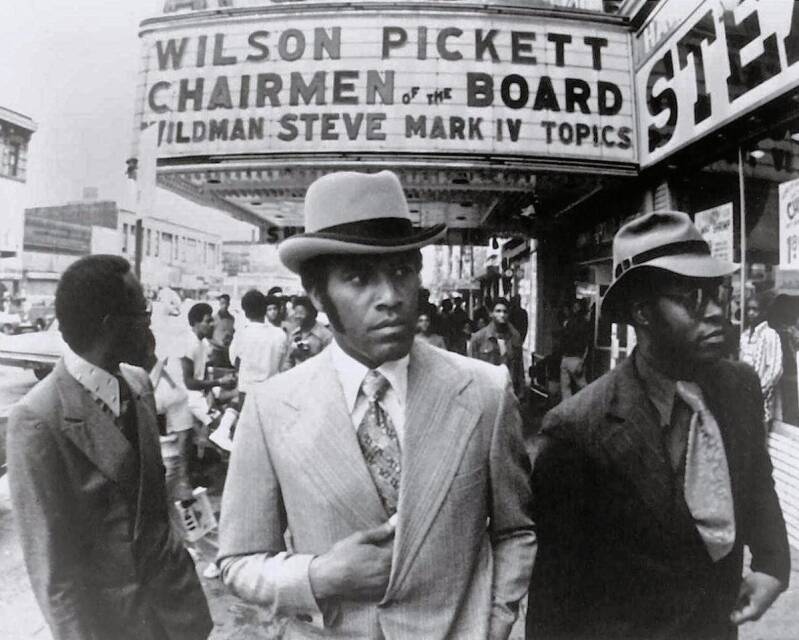

The Part That Rarely Gets Told: Community Protection & Resistance

Here’s where things get complicated—and where facts matter more than comfort.

Bumpy Johnson also:

- Paid rent for struggling families

- Funded community events

- Protected Black-owned businesses from white mob exploitation

- Used his influence to reduce police harassment in Harlem

- Advocated—quietly—for better treatment of Black prisoners

He was not a civil rights leader.

He was not a savior.

But in an era when the state offered Black communities violence instead of protection, men like Bumpy filled a vacuum.

This does not erase the harm.

It explains why some saw him as a protector anyway.

Survival vs. Morality: When Choices Are Not Equal

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: privilege determines morality more than we like to admit.

If you:

- Had access to education

- Lived in a safe neighborhood

- Were not targeted by racist policing

- Had generational wealth or even basic stability

Then your “good choices” were never made under threat.

Systemic racism—redlining, job exclusion, mass incarceration, underfunded schools—didn’t just limit opportunity. It engineered desperation.

For many Black men in early- to mid-20th-century Harlem, the illegal economy was not a rebellion—it was one of the only economies available.

That doesn’t make crime righteous. But it does make judgment shallow when stripped of context.

The Cost of Romanticization

When we glamorize gangsters, we:L

- Erase victims

- Normalize violence as power

- Ignore systemic failure

- Teach audiences that domination equals success

Worse, we consume these stories while doing little to dismantle the conditions that still create them.

We love the outcome.

We refuse responsibility for the cause.

Holding Two Truths at Once

Bumpy Johnson can be both:

- A man who helped his community in specific, material ways

- A man who caused immense harm through violence and drug trafficking

Acknowledging one does not cancel the other.

The real failure isn’t in refusing to idolize him.

It’s in refusing to ask why society keeps producing men like him—and why we keep rewarding their stories instead of preventing their necessity.

Finale

Romanticizing gangsters is easy.

Interrogating privilege is not.

If we truly care about justice, we have to stop pretending everyone starts from the same place. We have to stop confusing survival with moral failure. And we have to be honest about how many “criminals” were simply people whose potential was crushed long before they ever made a choice.

Understanding isn’t excusing.

Context isn’t absolution.

But without both, truth stays incomplete.

Add comment

Comments