By Yasmin Chaudhary — The Inkwell Times

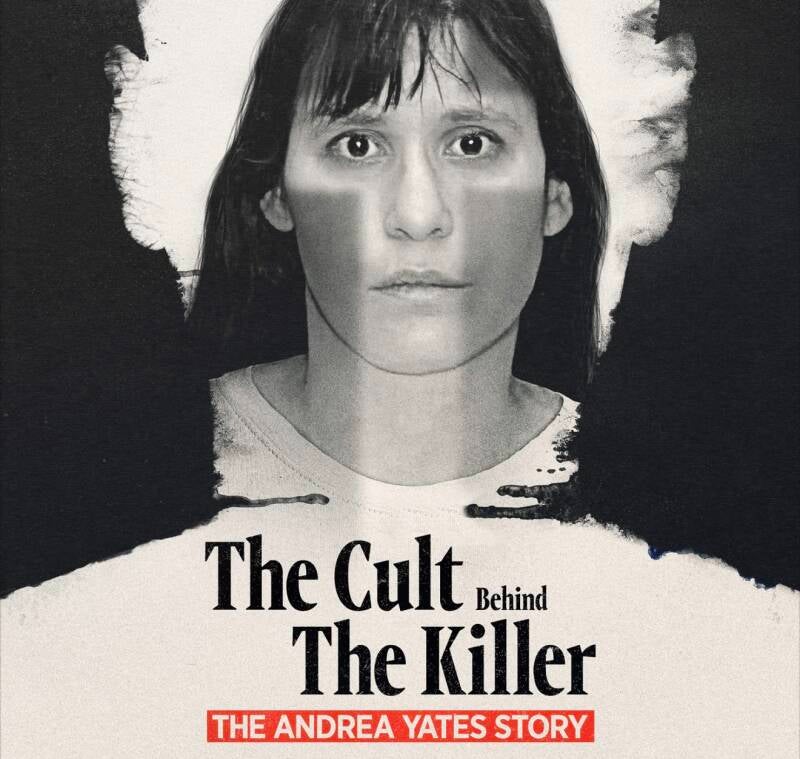

On a quiet June morning in 2001, five children were found dead in a Houston home. Their mother, Andrea Yates, calmly called police and reported what she had done. The crime shocked the nation and was immediately framed as the unthinkable act of a “monster mother.” But that framing ignored a far more disturbing reality — one rooted not only in untreated mental illness, but in a rigid, extremist belief system that operated less like faith and more like control.

Andrea Yates did not act in a vacuum. And she did not arrive at that moment alone.

A Family Shaped by Absolutism

Andrea Yates was raised Catholic and later married Rusty Yates, an engineer who embraced an extreme form of evangelical Christianity. Rusty became deeply influenced by the teachings of Michael Woroniecki, a self-styled street preacher whose doctrines emphasized sin, damnation, female submission, and the belief that children could be eternally condemned if raised by a “sinful” mother.

Woroniecki’s beliefs were not formally recognized by any mainstream denomination. Yet his influence on the Yates family was profound. The family lived an isolated life: homeschooling the children, limiting outside contact, rejecting modern medical guidance, and adhering to rigid gender roles in which Andrea bore sole responsibility for childcare and spiritual purity.

Experts later described the environment as ideologically coercive, a hallmark of cult-like systems — even without a formal cult structure.

Severe Mental Illness, Ignored and Minimized

Andrea Yates suffered from severe postpartum psychosis, a rare but dangerous condition. After the birth of her fourth child, she experienced hallucinations, suicidal ideation, and delusions. She was hospitalized multiple times and attempted suicide twice.

Doctors warned Rusty Yates that Andrea should not have more children and should never be left alone with them. Despite these warnings, she became pregnant again.

Even as her condition deteriorated — marked by catatonia, refusal to eat, and fixation on religious punishment — the family’s belief system reframed her symptoms as moral failure rather than illness. Medication was reduced. Supervision was relaxed. The pressure on Andrea intensified.

Mental health professionals later testified that Andrea believed her children were doomed to hell because she was a “bad mother” and that killing them was the only way to save their souls.

June 20, 2001

On the morning of June 20, after Rusty left for work, Andrea methodically drowned each of her five children in the family bathtub. She then called police and her husband, stating calmly that she needed help.

There was no attempt to flee. No confusion about what she had done.

What followed was one of the most polarizing criminal cases in modern American history.

Trial, Misinformation, and Reversal

Andrea Yates was initially convicted of capital murder in 2002 and sentenced to life in prison. During the trial, prosecutors relied heavily on testimony from psychiatrist Dr. Park Dietz, who falsely claimed that a television episode had depicted a similar crime — a claim later proven untrue.

In 2006, the conviction was overturned due to this false testimony. At retrial, Yates was found not guilty by reason of insanity and committed to a state mental hospital, where she remains today.

The legal system eventually acknowledged what mental health experts had argued from the start: Andrea Yates was profoundly psychotic at the time of the killings.

The Role of Ideology: Where Responsibility Extends

While Andrea Yates bears legal responsibility for the deaths of her children, the case forces a deeper question: How much responsibility lies with the system that shaped her reality?

• A belief structure that framed mental illness as sin

• A culture that glorified female suffering and submission

• A husband who ignored repeated medical warnings

• A community that equated obedience with righteousness

These are not isolated factors. They mirror patterns seen in coercive religious environments, where autonomy is stripped away and dissent — even medical — is treated as spiritual failure.

Calling this merely a tragedy of mental illness misses the full picture. This was a failure of intervention, of accountability, and of recognizing how extremist belief systems can quietly function like cults — without compounds, uniforms, or leaders with official titles.

Why This Story Still Matters

More than two decades later, the Andrea Yates case continues to be cited in discussions of postpartum mental health, religious extremism, and domestic isolation. Yet it is still too often reduced to shock value.

The real lesson is not about fear — it’s about prevention.

- Listening to medical professionals

- Recognizing coercive control, even when it wears religious language

- Treating mental illness as a medical emergency, not a moral failing

Andrea Yates’ story is not one of simple evil. It is one of unchecked ideology, untreated illness, and the devastating cost of ignoring warning signs.

And it serves as a reminder: when belief systems override care, the consequences can be irreversible.

Add comment

Comments